The UK economy faces long term challenges. Economic growth in the UK economy has slowed in recent decades. Despite positive progress, much more action is needed to tackle climate change. Economic infrastructure can play a key role in overcoming these challenges. Effective infrastructure can support growth in the economy by cutting costs and better connecting people and places. Decarbonising key sectors such as power, heat, and transport is critical to meeting climate targets; around two thirds of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions come from economic infrastructure.

Government’s progress on implementing the Commission’s recommendations this year has been too slow. Positive progress has been made in rolling out gigabit broadband, increasing the amount of renewable electricity generation, continuing to implement further devolution, and developing plans to increase water supply. But in a range of other areas government is off track to meet its targets and ambitions: more uncertainty has been created around the timeline for delivering High Speed 2, energy efficiency installations are too low, comprehensive policy is not in place to meet the government’s target on decarbonising heating, the National Policy Statements for energy have still not been updated, recycling rates continue to plateau, and per person water consumption remains too high.

To get back on track the Commission recommends government embed four key principles in its policy making over the next year:

- develop staying power to achieve long term goals

- fewer, but bigger and better interventions from central government

- devolve funding and decision making to local areas

- remove barriers to delivery on the ground.

The country faces economic challenges

Slow growth of the country’s economy has been a persistent issue in recent decades. The UK’s average annual growth in Gross Domestic Product since the 2007-2008 financial crisis has been one per cent, compared to 2.5 per cent in previous decades. Since the early 2000s, UK productivity has fallen further behind comparator countries such as France, Germany, and the United States. Alongside this, the UK economy also continues to suffer from profound and persistent regional inequalities. London is the only major city in the UK that has above average productivity. Although even in London, productivity growth has slowed significantly since the financial crash.

Part of the reason for the UK’s slow growth is low levels of investment. Since 1980, the UK has invested, as a share of Gross Domestic Product, less than comparator countries such as France, Germany, and the United States. Ambitious and stable policy from government, alongside effective regulation, is needed to facilitate private sector investment in the country’s key infrastructure sectors. Improving governance structures by enhancing devolution and removing barriers in the planning system will ensure increased investment is spent wisely and quickly.

Low levels of investment are also a challenge for reaching net zero. To meet its legally binding climate targets, the UK must reduce its overall greenhouse gas emissions by 78 per cent compared to 1990 levels by 2035, and to net zero by 2050. This will require significant investment across a whole range of activities, from heating homes to driving cars. Doing so will also help keep the UK at the forefront of international competition in some areas. Over 130 countries, comprising over 90 per cent of global gross domestic product, now have a net zero target set or under discussion.

Recent years have also demonstrated the challenges of underinvestment in resilience. Heatwaves in 2022 exposed fragility in the UK’s water resources, and labour shortages and extreme weather events have disrupted the rail network. Many of these risks will become more severe in the face of a changing climate, and action to enhance resilience is becoming more pressing.

Infrastructure is a key part of the solution

Good infrastructure facilitates growth. Improving the quantity and quality of infrastructure services will lower costs for households and firms in the medium to long term. Transport and digital infrastructure support efficient housing and labour markets, allowing people to live and work in different locations. And infrastructure also directly enables productivity enhancing technological change, for example better mobile and broadband networks were critical for the emergence of new online services. Tackling long standing regional economic disparities will also require increased investment in infrastructure.

Moreover, large scale investment in infrastructure, both public and private, is essential to achieving a net zero economy. In the UK, climate change is primarily an economic infrastructure challenge, with two thirds of emissions coming from the six sectors in the Commission’s remit. Estimates from the Climate Change Committee suggest up to £50 billion of investment will be needed each year for the next 25 years for the UK to reach net zero. Further investment will also be needed to increase resilience and adapt to the growing risks from flooding and drought driven by climate change.

Ambitious long term targets

In 2018 the Commission published the first National Infrastructure Assessment. This identified the country’s long term infrastructure needs and set out a series of actions for the government to take to secure the required investment. The Commission has followed the National Infrastructure Assessment with other studies containing recommendations across many infrastructure challenges.

The National Infrastructure Strategy, published in 2021, is a detailed and comprehensive approach to infrastructure policy responding to the Commission’s Assessment. It set out a series of policy decisions intended to support growth and put the UK on the path to a net zero economy. The Strategy was intended to endure, aiming to tackle entrenched policy challenges with a long term approach. As HM Treasury argue: “stronger economic growth requires a long term plan and commitment to see it through – there are no quick fixes to the challenges the UK faces.”

The government has built on the National Infrastructure Strategy with other key strategies and has now set clear long term goals in many critical areas. The Net Zero strategy was published in 2021, the Environment Act was passed in 2021, and the Levelling Up White Paper and subsequent Bill set out a series of key missions to deliver over the next decade.

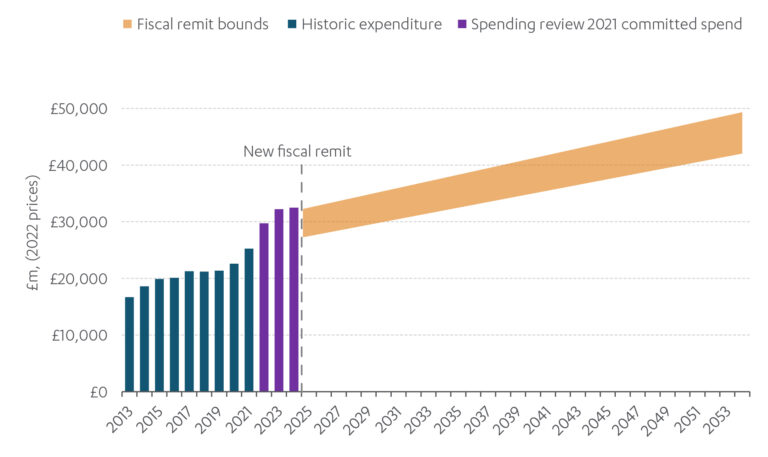

At the 2021 Spending Review, the government backed these high level ambitions with a funding commitment of £100 billion to support economic infrastructure from 2022-23 to 2024-25. This was re affirmed at the 2022 Spending Review (figure 1). However, over the last two decades government has frequently under delivered on spending commitments; it is critical this time that it follows through. The government has signalled a longer term commitment to investing in economic infrastructure by increasing the Commission’s fiscal remit, the technical guidance on how much public investment the Commission can recommend, to 1.1 – 1.3 per cent of GDP each year from 2025 to 2055 (figure 1).

Figure 1: Government is increasing spending on infrastructure in the short term, this must continue in the long term

Historic public expenditure on economic infrastructure 2013 to 2021, spending review commitments, and the Commission’s fiscal remit

Source: Commission calculations, HMT Public Expenditure Statistical Analyses (2022)

Note: Spending review 2021 committed spend of £100 billion is profiled based on department capital budgets set out in Office for Budget Responsibility’s March 2023 economic and fiscal outlook.

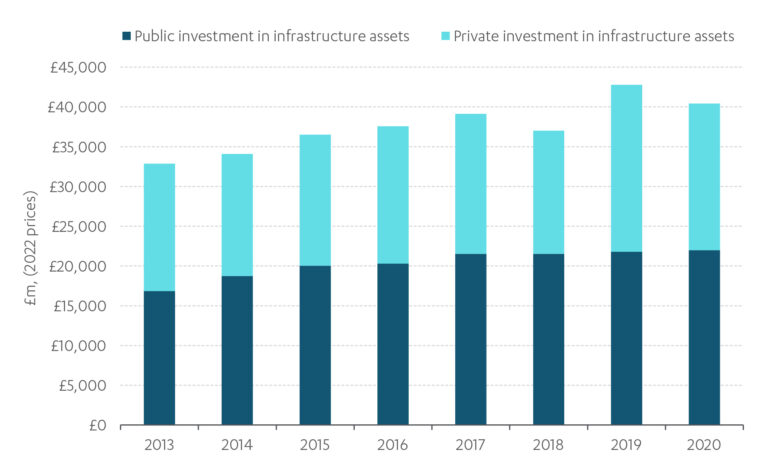

Private sector investment is also critical for meeting the government’s long term targets on infrastructure. In recent years, public and private investment in economic infrastructure assets has been broadly similar, with annual public investment around £20 billion and private sector investment around £18 billion (figure 2). The UK must remain an internationally competitive place to invest, at a time when the Inflation Reduction Act in the United States and the REPowerEU plan and Net-Zero Industry Act in the European Union make the investment environment more challenging. Ambitious and stable policy from government, alongside effective regulation, is critical for providing the private sector with the certainty it needs to invest.

Figure 2: Public and private sector investment in infrastructure assets is broadly equal

Public and private sector investment in infrastructure assets, 2013 to 2020

Source: Commission calculations

More consistent delivery from government is needed

The elements needed for successful delivery of the Commission’s recommendations and government’s ambitions are not currently all in place. Progress is being made. But significantly more action is needed to meet the Sixth Carbon Budget; carbon emissions need to fall from 447 MtCO2e in 2021 to 190 MtCO2e by 2035. Progress on delivering the ambitions set out in the Levelling Up White Paper is currently too slow. And barriers on the ground, such as the planning system, are slowing deployment across the board.

More detail on the Commission’s review of progress against its recommendations and government’s commitments in each of the key sectors within its remit is summarised below.

Digital

The government has made a genuine commitment to improve digital connectivity across the country. Delivery of gigabit capable broadband networks is progressing rapidly and, in 2022, gigabit capable coverage was extended to over 70 per cent of premises. This reflects significant increased investment from operators in recent years. If operators deliver on their published plans, and government maintains the £5 billion subsidy programme for under served areas, government will likely achieve its target to deliver nationwide coverage by 2030.

On mobile, 4G coverage from at least one operator now extends to around 92 per cent of the UK landmass, and the Shared Rural Network agreement should increase this to 95 per cent by 2026. However, challenges remain on securing investment for upgrading coverage on the rail networks.

Government must now set out a clear vision for 5G mobile networks in the upcoming Wireless Infrastructure Strategy. The long term commercial and strategic value of 5G will be determined by whether it becomes more than just a faster version of 4G, and whether it provides solutions to pressing problems.

Transport

The Commission has consistently recommended that local areas be given long term funding settlements for transport to aid planning and have greater control over investment. Moving away from the damaging system of competitive bidding for grant funding that erodes local capacity is critical.

Some progress has been made over the last year, including taking forward the commitment from the Levelling Up White Paper to transfer new powers, funding, and responsibilities to City Regions. The trailblazer deals and single multi year budgets announced for Greater Manchester and West Midland Combined Authorities are exemplars. The commitment to provide a second five year funding deal for England’s largest Mayoral City Combined Authorities for 2027-28 to 2031-32 will support long term planning. However, devolution must stretch across the whole country not just to major city regions. Progress empowering local authorities and helping them build capacity and capability must continue.

The government has committed to supporting the West Yorkshire Combined Authority to plan and build a mass transit system at an indicative cost of around £2 billion. While this is positive, it falls short of the ambition for major urban transport investment the Commission set out in the National Infrastructure Assessment.

Progress on major transport projects connecting major cities is mixed. The Integrated Rail Plan provided clarity with a long term plan for rail in the North and Midlands. It included a commitment to invest £96 billion to build new high speed lines and upgrade and electrify existing lines. Recent delays to delivery of High Speed 2 will inevitably delay the benefits of greater connectivity that are crucial to the economies of the North and Midlands – government must act to create a greater sense of certainty around the whole project and ensure that there are no delays to the current timetable for High Speed 2 services reaching Manchester. Action on the Cambridge-Milton-Keynes-Oxford arc remains slow and the government’s long term commitment to the road infrastructure needed to unlock growth in the region is unclear. If this does not change, the country will miss a significant growth opportunity.

Transport remains far too carbon intensive. In 2021, emissions from surface transport were 101 MtCO2e. This needs to fall to around 30 MtCO2e by 2035 to meet the Sixth Carbon Budget. In 2022, government published critical strategies on decarbonising road transport, which support the government’s expectation of 300,000 public charge points and near 100 per cent electric car and van sales by 2030. But only 37,000 public charge points are currently installed. There are just eight years left to meet government’s target; a rapid increase in electric vehicle charge point installations is now needed to support the adoption of zero emissions vehicles.

Energy

The UK is too reliant on natural gas: a high cost, high carbon, and insecure source of energy. In 2022, the sharp rise in gas prices prompted by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine increased the cost of energy and jeopardised security of supply. The government is now directly subsidising the energy consumption of households and businesses, setting prices for the average household at £2,500 per year between October 2022 and June 2023. Relying on natural gas for electricity and heating leaves the energy system far too carbon intensive. In 2021, emissions from the power and heating system were 135 MtCO2e, this needs to fall to around 50 MtCO2e by 2035.

The Commission recommended that the UK should have a highly renewable electricity system, and good progress continues to be made delivering this. In 2022, 40 per cent of electricity was generated by renewables, up from around ten per cent a decade earlier. This has been driven by the government maintaining its contracts for difference policy, which provides revenue certainty and de risks investment. Renewable electricity, through offshore wind, onshore wind and solar, is now cheaper than producing electricity with natural gas. However, there are only 12 years to realise the government’s aim of a decarbonised electricity system by 2035. Barriers to further renewables deployment, such as securing transmission grid connections, must urgently be addressed to stay on track.

Little progress has been made on energy efficiency or heat this year. A concrete plan for delivering energy efficiency improvements is required, with a particular focus on driving action in homes and facilitating the investment needed. And while the government has set targets for decarbonising heating, these are not backed up by policies of sufficient scale to deliver the desired outcomes. Key policies remain missing, and government funding is insufficient to deliver the required change. In 2021, over 1.5 million gas boilers were installed. The government has set an ambition for at least 600,000 heat pumps to be installed each year by 2028, but only around 55,000 were installed in 2021. Unless the growth rate of installations increases significantly , the 600,000 heat pump installation target will be missed. These challenges must be urgently resolved to meet the Sixth Carbon Budget.

Flood resilience

Around two million homes and properties in England are in areas at risk of flooding from rivers and the sea, and climate change means the risk is growing. In line with the Commission’s recommendations, government investment in measures to reduce the risk of flooding has doubled and policies have been revised to emphasise catchment based planning, green infrastructure, and property level resilience. But government has yet to specify measurable long term targets for flood resilience. Until it does so, policies and investment are unlikely to fully address the flood risk challenges the Commission identified in the first Assessment.

Last year, the Commission published a study on surface water flooding. Over three million properties are currently at risk of suffering surface water flooding, and 325,000 are at high risk with at least a 1 in 30 chance of flooding every year. In the coming decades the number of properties in areas that are high risk could increase by up to 295,000, due to growing risks from climate change, new developments increasing pressure on drainage systems and the spread of impermeable surfaces from paving over gardens. The report sets out the need to better identify the places most at risk and reduce the number of properties at risk. This will mean devolving funding to local areas at the highest risk and supporting them to make long term strategies to meet local targets for risk reduction. The Commission expects government to respond to these recommendations this year.

Water

The drought of summer 2022 demonstrated the risk of water shortages due to climate change and population growth. In the first National Infrastructure Assessment, the Commission recommended addressing the growing risk of water shortages through a ‘twin track’ approach: to reduce demand and increase supply. To deliver this, the Commission called for ambitious targets for leakage reduction, compulsory smart metering, the creation of additional supply and a national water transfer network.

If implemented, industry plans are ambitious enough in scale to meet the Commission’s recommendations on leakage and new supply. And some progress has already been made, with leakage rates have fallen from around 3085 mega litres per day in 2017-18 to 2755 mega litres per day in 2021-22. However, there is still a long way to go to meet the target of reducing leakage by 50 per cent by 2050. To meet ambitions on supply, current plans suggest that at least 12 nationally significant infrastructure projects will need to be consented by 2030, so it is critical the planning system is fit for purpose and progress is made rapidly. Longer term demand reduction is dependent on government action, and it is not clear that current government policies on water efficient homes and water efficient product labelling are sufficient to achieve the 110 litres per person per day consumption target by 2050.

Waste

Government must do more to increase waste recycling rates. The Resources and Waste Strategy and the Environment Act 2021 indicated an ambition to incinerate less and recycle more. In line with the Commission’s recommendations, government set targets to recycle 65 per cent of local authority collected waste by 2035, 62 per cent of plastic packaging by 2030, and achieve universal food waste collection by 2025. However, despite having clear overall targets, recycling rates have stagnated since the mid 2010s: local authority collected waste recycling rates have plateaued at around 40 per cent, as have plastic packaging recycling rates, and only around 40 per cent of local authorities currently have separate food waste collections. Unless clear rollout plans are now put in place, these recycling targets will be missed, and the sector will remain a major source of carbon emissions.

Getting back on track

To get back on track, government needs to take a more consistent and committed approach to policy and delivery. Government’s infrastructure ambitions are essential. But they are also challenging to deliver.

The Commission recommends that going forward, government should embed four key principles in its approach to infrastructure policy making:

- Develop staying power to achieve long term goals. Continued chopping and changing of infrastructure policy creates uncertainty. This uncertainty creates a cost for business and delays or deters investment. For example, government’s stop start approach to energy efficiency policy has led to low rates of installations over the past decade; and uncertainty associated with the future of the Cambridge-Milton Keynes-Oxford growth arc has likely inhibited growth and deterred inward investment. In contrast, where government has created policy stability, investment has followed. For example, the contracts for difference mechanism has provided certainty to developers and resulted in rapid deployment of renewable electricity generation. Similarly, government’s stable policy on broadband, alongside network competition, facilitated significant investment leading to gigabit capable coverage increasing from five per cent of premises in 2018 to over 70 per cent of premises in 2022. Government must create greater certainty around key projects, such as High Speed 2, to follow through on its long term goals.

- Fewer, but bigger and better interventions from central government. Meeting the challenges of net zero requires clear strategic focus. The need for rapid progress to tackle climate change is becoming ever more apparent; the risk of delay is now bigger than the risk of building more infrastructure than is needed. But government continues to expend too much effort on many small scale funding interventions and repeated consultations, trying to maintain optionality in all areas. This leaves key strategic policies — such as business models for hydrogen and carbon capture and storage, taking a decision on the role of hydrogen for heating, and putting policy in place for getting off gas — unfinished. Going forward, government will need to take some strategic bets; such as the recent commitment to £20 billion funding to support key new energy technologies. Making small steps forward in all directions will not bring about the scale of change in infrastructure needed to meet the Sixth Carbon Budget and deliver a net zero economy. Government must now focus on the small number of areas where it can have a big impact and make bold decisions.

- Devolve funding and decision making to local areas. Long term planning and funding decisions taken at the right spatial level will better reflect local economic and social priorities and avoid distorted incentives created by pursuing myriad national grants. Evidence suggests that with good quality institutions and limited fragmentation across economic areas, devolution is positively associated with productivity and growth. Moreover, devolving decision making allows central government to stay more focused on key national priorities. Government has committed to extending and simplifying devolution across the country and giving local leaders greater control over how funding is spent. Where progress has been made, for example with the extension of Metro Mayors, positive impacts are being seen. The trailblazer deals and single multi year budgets announced for Greater Manchester and West Midland Combined Authorities are exemplars. Government must complete the move away from competitive bidding processes and implement flexible, long term devolved budgets for all local transport authorities. The missing link is fiscal devolution and allowing greater revenue raising powers at a local level. Local leaders should be able to fund as well as find their own local infrastructure solutions. This would create stronger economic incentives to drive local economic growth and provide resources for city regions and Mayoral Combined Authorities to contribute to the costs of improving local infrastructure. The Commission is looking at the scope for transport user charges to support local transport infrastructure – and this principle could be applied to areas such as business rates growth retention.

- Remove barriers to delivery on the ground. The planning system for handling nationally significant infrastructure projects has slowed in recent years, with the timespan for granting Development Consent Orders increasing by 65 per cent between 2012 and 2021. Not only does this mean that much needed infrastructure is not getting delivered, but it also adds significant cost which will ultimately be paid for by consumers and taxpayers. The system needs to return to the situation in 2010 where projects were typically taking two and a half years to achieve consent. Recent publication of the draft National Networks National Policy Statement is a step in the right direction. Government must now publish the final National Policy Statement for Energy. Decarbonising the electricity system will require over 17 transmission projects to receive development consents in the next four years, a fivefold increase on current rates. The Commission will publish its study on the infrastructure planning system shortly and the Commission hopes government will rapidly progress its recommendations.

Alongside these four key principles to embed in policy making, the Commission is calling on government to progress ten actions over the next year (figure 3). These actions will help get government back on track to delivering the Commission’s recommendations and tackling the challenges of net zero, regional growth, and climate resilience.

Figure 3: Government actions for the year ahead

| Theme | Targeted action for the year ahead |

|---|---|

| Supporting growth across regions | Move away from competitive bidding processes to give local areas more flexibility and accountability over economic growth funds, and implement flexible, long term devolved budgets for all local transport authorities |

| Demonstrate staying power by progressing the Integrated Rail Plan for High Speed 2 and Northern Powerhouse Rail and remaining committed to the £96 billion investment required | |

| Follow through on commitments made in 2018 to the Cambridge-Milton Keynes-Oxford growth arc, by setting out how the road and rail infrastructure to support new houses and businesses will be delivered | |

| Net zero and energy security | Deliver a significant increase in the pace of energy efficiency improvements in homes before 2025, including tightening minimum standards in private rented sector homes, to support delivery of the government’s target for a 15 per cent reduction in energy demand by 2030 |

| Remove clear barriers to deployment in the planning system by publishing National Policy Statements on energy to accelerate the consenting process for Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects | |

| Accelerate deployment of electric vehicle public charge points to reach the government’s expectation of 300,000 by 2030 and keep pace with sales of electric vehicles | |

| Ensure that Ofgem has a duty to promote the delivery of the 2050 net zero greenhouse gas emissions target | |

| Building resilience and enhancing nature | Implement schedule 3 of the Flood and Water Management Act 2010 this year and without delay |

| Rapidly put in place plans to get on track to reduce per person water consumption to 110 litres per day by 2050, starting by finalising proposals on water efficiency labelling and water efficient buildings this year | |

| Initiate a step change in recycling rates, including for food waste, by proceeding with the Consistency of Recycling Proposals, and finalsing the Extended Producer Responsibility and Deposit Return Scheme |

The Next National Infrastructure Assessment

Later this year the Commission will publish the second National Infrastructure Assessment. This will set out a series of further recommendations for government to meet the challenges of delivering growth across regions, meeting net zero, and enhancing climate resilience and the environment.