Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt looks after thousands of listed buildings, monuments and assets and helps preserve Wales’ heritage.

Now, Cadw is marking its own bit of history – its 40th birthday – 75 years since the first historical buildings were listed in Wales.

Meaning “protect” or “to keep” in Welsh, Cadw was set up in the autumn of 1984, a joint agency of the Welsh Office and Wales Tourist Board, with the aim of conserving and promoting the nation’s heritage to visitors.

It took on responsibility for 10,500 listed buildings and 2,700 monuments from the Department of the Environment and – since then – another 20,000 assets have been given protection through listing.

The first wave of protected heritage assets came in May 1949 and included the main building at Bangor University and Bangor Town Hall – the old Bishop’s Palace with 16th Century origins.

Powys has the most listings of any Welsh county – nearly 5,500 – followed by Wales’ smallest county, Merthyr Tydfil, which reflects its rich industrial heritage.

The furthest flung is on a rock 16 miles (27km) off the Pembrokeshire coast – the Smalls lighthouse.

We’ve created a map above, which shows where all the 30,100 listings are – you can click on the map to find out a bit more about them.

As well as more than 1,000 churches and 670 chapels, there are more than 300 pubs, 94 castles and 25 lighthouses.

There are also about a dozen theatres and cinemas, 13 animal drinking troughs, 11 bandstands in parks and assorted post boxes, as well as five cannon, the walls of Swansea prison and a hut at an old prisoner of war camp at Bridgend.

Other curiosities include an old windmill near a Pembrokeshire airfield, which was adapted as a machine gun post during World War Two.

Nearly half the listed assets are people’s homes.

In Barry, Vale of Glamorgan, there are 57 listings, including the lifeboat house and a public toilet.

The latest to get protection is Barry Island resort’s railway station, described as a “good example of a late 19th Century railway station building that has survived relatively intact”.

Gwilym Hughes, head of Cadw, said: “It’s unaltered which makes it special and it reflects late-Victorian Barry, which was created as a new town at the time the station was built, it was only about 10 years old.

“It was founded in 1884 when the docks were starting to be built and the town grew massively from a small hamlet to a town of 30,000 people within about 10 years.

“This station reflects that story of this incredible growth of this industrial town and port.”

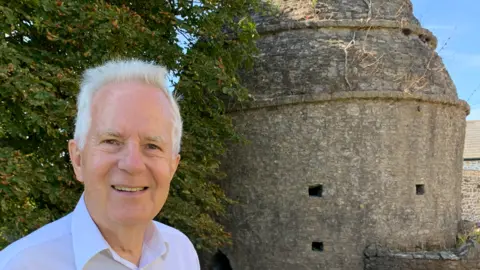

Dennis Clarke lives at The Court in Cadoxton in Barry, which is home to a Grade I listed dovecote – the only Grade I listed building in the town – dating back more than 800 years.

“In those days you didn’t have a dovecote unless you were one of the mega rich,” he said.

“It would have been a status symbol but also a very important source of all sorts of things, including meat, feathers, eggs and even gunpowder was kept inside it.

“There are 750 nesting holes for birds, that means there would have been around 1,500 birds and as many fledglings they produced inside it.

“Just imagine the noise and the smell the servants had to deal with. We don’t get any birds in here now, so I don’t have to worry about any mess to clear up.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDennis moved into the property nearly 10 years ago and gives Cadw-approved guided tours.

He said one historian described it as having more history per square inch than anywhere else in Barry.

It is the only part of the original manor house still surviving and Dennis said the legend was that it was burned down by Owain Glyndwr – the last native Prince of Wales.

“It was rebuilt by the owners in the 15th Century but then fell into disrepair and the Grade II rectory which is now our home was built in 1873. It’s brilliant that the dovecote has survived.

“It’s a privilege to live here but what goes with that privilege is the responsibility to look after it, so the next people who come along after we’ve passed will hopefully feel the same way and continue to look after it.”

Forty years from its creation, Cadw’s work continues.

More than 50 Grade II listings have been made since 2023, including 13 this year.

The latest is Christ The King catholic church in Builth Wells, Powys, which dates back to the 1950s.

It was built to the specifications of its parish priest Father John O’Connell, who was a scholar and also wrote a book on church building and had special interest in its design.

Three other church buildings have been listed this year in Carmarthenshire, Pembrokeshire and Swansea.

A garage and lodging believed to be used by chauffeurs driving aristocratic tourists to Colwyn Bay is another new listing, dating from Victorian times.

Also, three milestones designed by Thomas Telford on the A5 Holyhead road in Gwynedd and Conwy have been given protection.

Under interim protection for intended listing is the 1970s modernist Aberystwyth arts centre and university library.

In 2023, notable Grade II listings were given to St David’s Hall in Cardiff and Plas Menai outdoor education complex in Gwynedd.

There were also listings for a rare 19th Century horse trough in Stackpole, Pembrokeshire, and the Harlequin puppet theatre in Rhos-on-Sea, as well as the former home near Montgomery of songwriter Jerry Lordan, who wrote hits for The Shadows, and whose house came with its own cave.

Mr Hughes said Wales had one of the highest proportions of historic buildings in Europe, adding it was “extraordinary” that about 30% of all residential buildings predate World War One.

He added: “We’ve listed some strange things over the years from the apple kiosk in the Mumbles, which is a quirky sculpture, to a blue police telephone box which is also listed in Newport and another example in Tredegar, we’ve listed a lump of coal.

“Well, it’s not just a lump, it’s a 15-tonnes lump of coal. That’s the largest bit of coal that has ever been mined and sculpted so that has been listed.

“Only in Wales!”